#2 in my definitive ranking of David Lynch’s films.

This movie has convinced me that David Lynch does not make difficult movies. He makes movies that require the audience’s attention and investment, but the central idea isn’t some obtuse thesis on an obscure philosophical idea. There’s always an intensely human core to his films, and I don’t think that these human ideas are particularly difficult to figure out. If Lynch had a single character say a single line that explained what was happening at any point in the film, people wouldn’t call him a mysterious artiste that’s difficult to dissect, they’d call him an obvious charlatan who can’t help browbeating the audience with his point. That’s how obvious I find the central ideas.

Now, that really feels like it’s filled with a negative connotation, but I really don’t mean it like that. I find Lynch’s films rich and wonderful to sit through as they demand my attention to delve through the assorted and related images to come to a central point. These aren’t random images with no meaning to anyone but Lynch. These are emotionally based ideas playing out in the logic of dreams, and the central idea at the heart of Lost Highway is guilt.

Fred is a jazz musician married to Renee. One night he goes to the club to play and she meekly states that she’s going to stay home to read. This simple act sends Fred into a paranoia infused descent as he ends up seeing Renee’s deception wherever he turns. It’s made all the worse when videotapes start getting left on their front steps, videotapes that contain footage of first the exterior of their house then the interior of their house ending with a view of the two sleeping in bed. They go to a party where Fred sees Renee hanging off of a male friend, Andy, a little too long, and he recalls a time when they seemed to leave the club together. This is all derailed with the Mystery Man approaches him, hands Fred a cell phone, and tells him to call Fred’s house where the Mystery Man also is.

It’s this sort of stuff that people get can get trapped in, and it’s not really all that important. Is the Mystery Man literally in both places at once? Is he even really there? Does he even exist? These don’t matter. The literal actions matter less than the emotional reality that they create, and what they create for Fred is him questioning the very nature of his reality, disassociating him from his actions, so that when he sees the third and final videotape that ends with Fred kneeling over Renee’s mutilated corpse. The action quickly skips forward through Fred’s trial that ends with him locked up in jail. This is a little less than halfway through the film, and suddenly everything changes. He suffers a massive headache, falls unconscious, and wakes up to discover that he’s someone else. He’s no longer a mid-30s jazz musician. Instead he’s a mid-20s mechanic. Not knowing how to explain how one man disappeared from a jail cell and another one appeared in it, the prison lets Fred, now called Pete, go, and the movie seems to start all over.

Pete, for a time, seems to be Fred cautiously interacting with everyone just in case he says something wrong, but he steadily becomes Pete completely, knowing Pete’s girlfriend, boss (Arnie, played by Richard Pryor in his final role), and the gangster customer Mr. Eddy. Mr. Eddy is almost a re-manifestation of Frank Booth from Blue Velvet, probably in no small part because Robert Loggia had arrived to his audition for Frank Booth, had to wait three hours only to find out that Dennis Hopper had already be cast, ending with a long tirade against Lynch to his face. Probably the single most entertaining moment of the whole movie is Mr. Eddy chasing after a tailgater, knocking him off the road, pistol whipping him, and then demanding that the man study a driving manual and follow the rules of the road.

A curious thing happens, though, when Mr. Eddy drops off his second car and the girl in the passenger seat is a blonde version of Renee named Alice. Both are played by Patricia Arquette, and there is little effort to explain the presence of this supposed twin. Steadily, she draws Pete into an affair, and the two are having sex around Mr. Eddy’s back, a seriously dangerous situation for both of them. Everything comes to a head when Alice entices Pete into a crime to break into Andy’s house which ends with Pete killing Andy in front of a picture of Andy, Mr. Eddy, Renee, and Alice.

How does this all tie together? Well, I believe that from the 55-minute point onward everything in the movie is a dream. Fred does not literally turn into Pete. Instead, Fred, consumed by his guilt, imagines a different reality where he is not himself, Renee is not herself (something Fred says to Renee early in the movie about a dream he’s had), and so Fred has not killed Renee. He’s the young, sexually adept man who is going to protect Alice from the gangster and pornographer (Andy), no longer the middle aged man who performs poorly in bed and has murdered his wife out of paranoid jealousy. Consumed by the heinousness of his actions, he creates an alternate reality where he’s younger, more virile, and saves Alice instead of killing Renee.

However, he can never escape who he truly is. Taken to a remove cabin with Alice to meet her fence in order to get rid of the valuables they’ve taken from Andy’s house, Alice vanishes and Pete becomes Fred again, meeting the Mystery Man again before Fred drives to his own house and delivers himself a message from the beginning of the movie.

What does all this mean? Looking at it from a purely emotional and sensorial point of view, Fred has found a way to cure himself of his guilt for what he did to Renee. Is he justified in doing it? Probably not, but it seems to be the only way that Fred can manage to continue on mentally. Laying it all out feels less compelling than the movie itself though, which plays out all of this subtly through image and sound without ever stooping to blatantly explain itself to the audience, leaving the joy of discovery to the audience. It’s a delirious descent into a nightmare tightly wound up in the main character’s mental state, and it’s wildly compelling as it plays out. The middle section, where Pete arises from Fred, almost feels like it’s meandering with no connection to the first hour of the film, but it all comes together in a shockingly tight narrative with surprising focus.

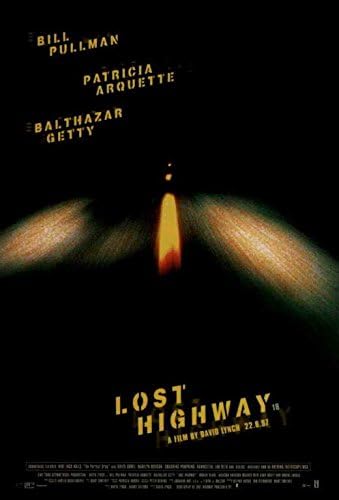

Tonally this represents a completely new direction for Lynch. Abandoning the melodramatic trappings of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Blue Velvet, and Wild at Heart, Lynch takes a much more understated approach with minimalist performances from everyone. Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette, and Balthazar Getty all deliver muted performances as they navigate this dreamlike landscape, the one exception being Robert Loggia as Mr. Eddy, of course. This is overall a quieter, more introspective film than anything Lynch had made since The Elephant Man, and I think it helps the final package achieve a certain power that it might otherwise not have in a more excitable atmosphere.

This is an experience, a complete look into the mind of a man driven mad by his own actions, desperate for a way to absolve himself of his guilt. This is Lynch using all the tools of cinema to bring his unique vision to reality.

Rating: 4/4

An interesting aspect is how many of some of the memorable scenes actually happened in Lynch’s life (the beginnings, anyway). The “We’ve met before, haven’t we?” dialogue was when Lynch met Dean Stockwell, and the tailgating thing happened when he and Michael Anderson were driving somewhere. After the tailgater passed, Anderson said something like, “That guy, huh,” and Lynch said “He’s lucky I didn’t pull him over, he’d have gotten his.”

There’s a DVD released around the time of this film called “Pretty As A Picture” which has a number of these stories.

LikeLike

May have been clear to you, but totally opaque to me. Your explanation seems feasible, but using that device of switching gears part way through the movie – a new character who is the old character – as way to explain an inner state was so obscure to me that instead of hitting me emotionally just left me going Huh? I guess I need things to be a bit more obvious.

LikeLike

I think the audience needs to ask the question, “Why is this guy suddenly a different person?” and come to the quickest solution: It’s not a different person, that’s absurd because it would mean that everything up to this point has been without purpose to this story.

From there, you start remembering things like the conversation between Fred and Renee where Fred recalled his dream about how Renee looked like herself but was different.

If everything is connected and has purpose within the story, then that greatly reduces the number of possible explanations for the weird events.

LikeLike

No mention of Robert Blake? I thought he was the most memorable performance of the whole film. Not to mention the layers of irony of casting a man most, including me, believe had his own wife killed in this movie.

I consider this movie a nightmare and it’s the only way I can really endorse it. I’m far too literal in general to enjoy movies that don’t make sense. There are exceptions and Lost Highway might be one of them.

LikeLike

The Robert Blake connection is so weird. He is fascinating as The Mystery Man, and then he goes on to be Fred in real life.

I think you have the right read. It’s a descent into a nightmare where the subconscious fights itself. It’s sort of like Suspiria but more tied to the central character’s actual emotional journey instead of just a demonstration of nightmare logic (that I love, by the way).

LikeLike